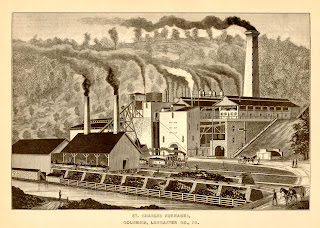

![]() |

| Libby Prison in Richmond, 1865 (Source) |

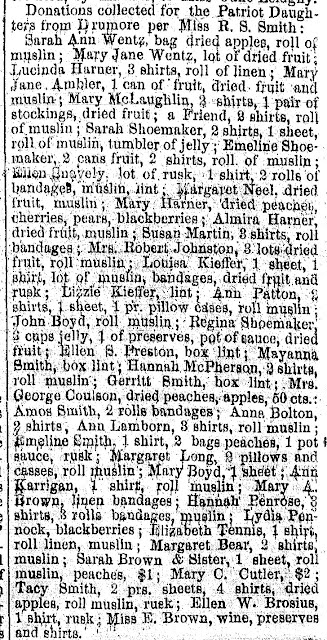

In this post, I republish an exciting account of David Miles' eleven months in Southern prisons that Miles gave to the editors of the Daily Evening Express upon his parole and return to Lancaster. See the full account here, which was published on August 11, 1864.![]() |

Lieut. Col. David Miles

(D. Scott Hartzell Collection, USAMHI) |

David Miles, the future lieutenant colonel of the 79th Pennsylvania, was born in Franklin County in 1831. By 1860, he had moved to Lancaster's Northwest Ward to work as a tinsmith with wife Mary and four children. Before the war, he was involved with the Lancaster Fencibles militia and apparently also worked to promote Lincoln's election, as William McCaskey mentions Miles as the marshal of "the great Lincoln Mass Meeting" (as a reference point for a type of hat McCaskey wished to have sent from Lancaster, 2/5/1865). Upon the organization of the Lancaster County Regiment, Miles would take the position of first lieutenant of Company B, 79th Pennsylvania. The departures in 1862 of Captains Kendrick, Duchman, and Druckenmiller opened the path for Miles to become lieutenant colonel, and he led the regiment's left wing with distinction at the Battle of Perryville.

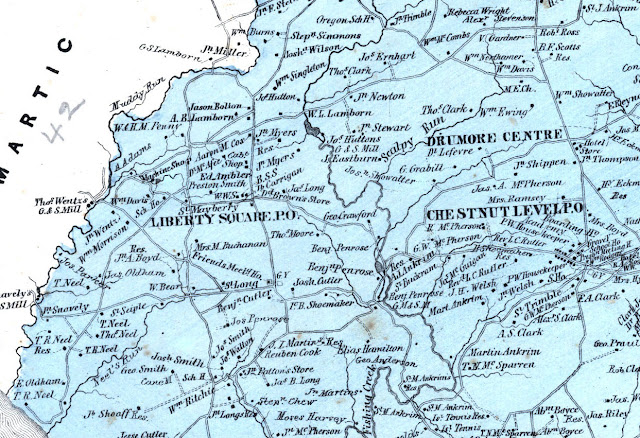

Just after the dark on September 19, 1863 -- the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga -- the 79th Pennsylvania advanced through dense woods to plug a hole in the Union line. Commanding the left wing was Lt. Col. David Miles, who was mounted on horseback after breaking his leg in a fall from his horse back in May. As the Lancaster County Regiment moved forward, a combination of friendly and enemy fire caused the situation to rapidly deteriorate. The line broke and the regiment hastily retreated.

The hobbled Miles found himself dismounted in no man's land with his horse's reins in his hands. He lay on the ground to escape the bullets and eventually remounted after finding a stump to stand on. Due to a faulty sense of direction or the shifting battle lines, Miles rode into what he thought were friendly soldiers, only to be surrounded by Confederate soldiers who demanded his surrender.

For the next month, his fate was a mystery to the remaining soldiers in the 79th Pa, who feared the worst for him and his family. Capt. William G. Kendrick wrote his wife of the situation, "[Miles'] wife has five children and she is not able to walk and has nothing to live on, a terrible condition to be left in,

no life insurance." (10/14/1863, emphasis in original) Miles' self-described protege, Capt. William McCaskey, thought it a good idea for his brother to send his sister on a visit to Mrs. Miles to comfort her, but felt confident that Miles would turn up based on reports of another regiment nearby thinking that they saw him on the night of September 19.

By the time news of Miles' capture reached Lancaster and the 79th Pennsylvania, Miles had already spent two weeks as a resident of Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. Immediately after his capture on September 19, the Confederates had him and other prisoners march to a rendezvous point ten miles distant. Fellow captives John Shirk of Company E, 79th Pa, and

Lieut. John W. Thomas of the 2nd Ohio Infantry* provided the injured Miles with badly needed shoulders to lean on during this march. Miles and other Union soldiers made a journey by train and arrived at Libby prison -- an old tobacco warehouse -- on September 29, 1863.

The escape took place on the night of February 9-10, 1864, after weeks of tunneling by imprisoned Union officers. The total number of prisoners to escape was 109, of whom 59 succeeded in reaching Union lines. Miles joined Captain Hardy of the 79th Illinois and broke east for Union lines. The traveled an estimated 60 miles in a circuitous route, aided by local African Americans. While trying to pass the very last line of Confederate pickets, they were recaptured five days after they escaped. Miles was taken back to Libby prison and was confined in a hole for two days, but was spared further punishment due to his illness and rejoined the general prison population.

The next chapter in Miles' prison saga involved getting sent to Charleston, South Carolina, as a human shield, which was an upgrade from prisoner in Richmond as far as Miles was concerned. Upset about the bombardment of Charleston by Union forces, the Confederates placed the fifty highest ranking prisoners (which included Miles) in a jail and subsequently a relatively comfortable house in range of the Union shells. Miles claimed not to have felt any great danger but rather enjoyed the ability to purchase from market wagons and even to "play ball and exercise themselves" in a space set aside for that purpose.

![]() |

Tombstone of David Miles

Lancaster Cemetery |

Eventually, the controversy over the bombardment of Charleston and use of human shields came to a resolution, and a special exception to the no prisoner exchange policy allowed the Union officers in Charleston to be exchanged. Miles arrived home in Lancaster in early August 1864. Besides spending time with the editors of the

Express to get a full account that was published on August 11, the Lancaster Fencibles -- his old militia unit --

treated him to a supper on August 18. Miles made a celebrated return to the Lancaster County Regiment on the evening of October 29, 1864. Sgt. William T. Clark reported in his diary, "Lieut. Col. Miles looks very well. Crowds are continually around him, hearing of the suffering of Rebel Prisons."

Miles would lead the 79th Pennsylvania or its brigade for most of the rest of the war, most notably commanding a brigade at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina, where he was wounded. Overall, he seems to have been a courageous, competent, and highly-esteemed officer. The escape in which he participated gained national attention and provided another welcome positive distraction in what could have been a long winter of 1864 for Northern civilians and soldiers.

Notes:

* Both Shirk and Thomas have their own escape stories. Shirk went off to Danville prison and was part of a similar escape later in February 1864. He left his own account (and is mentioned in an account by John Obreiter of the 77th Pennsylvania), which I will feature in a future post. Thomas successfully reached Union lines in the escape from Libby prison. He was killed in battle on July 20, 1864, near Atlanta.